This video validates a blue courting robe once owned by Chief Crazy Horse. Harold White Horse Thompson, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, described the robe’s craftsmanship, cultural significance, and provenance. The article “Courting Robe of Chief Crazy Horse” provides more information about the history of this item: https://www.siouxreplications.com/extended-museum-articles/courting-robe-of-chief-crazy-horse.

Buffalo Hide Tipi Dedicated

A tradition of dedicating a special hide tipi during pre-reservation days was a ceremony using warriors to honor a recently completed tipi. During the Buffalo Days, veteran warriors were asked to imbue a hide tipi with their courage, fortitude, and integrity by walking across the spread-out buffalo hide cover. It was a great honor to be chosen for this occasion. Modern day warriors are military veterans who participated at the Veteran’s Day event at noon on November 18.

Dedicating new buffalo hide tipi with Charly Juchler singing honoring songs, while Jeff Iron Cloud walks behind the lead dancer.

The occasion was for the completion of my 67th hide tipi, before installing it in a Lakota exhibit. The hand-tanned tipi of sinew-sewn nine hides was embellished with full porcupine quillwork of a leader’s lodge. The celebration revived an ancient ceremony while notable Lakota families and veterans were alive to complete the special walk, prior to setting up the hide tipi.

The 14-foot buffalo hide tipi cover is 28 feet across for the walk by each of five warriors, accompanied with singing and drumming of Crazy Horse honoring songs. Each walked barefoot, or with new moccasins, across the hide cover, led by a dancer waving a historic Lakota carved wand (Owanka Onaesto). This ceremonial wand’s swaying was to solemnize the ground for the celebration. Each warrior wore a beaded blanket for their honoring walk.

Prior to a warrior’s walk, each recounted their military experience and Lakota Sioux recounted the deeds of their famous chief ancestors. Jeff Iron Cloud told of his great-grandfather, Knife Chief, “cousin” to Crazy Horse. He fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn and during the fighting was shot by a soldier. To stop the bleeding, Knife crawled by a plum thicket and used a plum from the bush to plug the hole. Francis White Lance told of his ancestry tied to the line of Crazy Horse. Francis mentioned earning his honorary doctorate, received from research showing Crazy Horse’s family tree. During the dedication, the military branches of the Army, Air Force and Marines were involved.

After the walking ceremony was conducted, the hide cover was placed on a travois and pulled where participants erected the dedicated tipi. The ceremony closed with a meal of buffalo stew and Lakota fry bread. The tipi was packed for its destination to the World Wildlife Heritage Museum in Concord, California.

The journey to making the tipi for the dedication began nearly fifty years earlier. The beginning resulted from a visit with Reginald Laubin about his The Indian Tipi book. I had published my Brain-Tanning the Sioux Way and we discussed a new craze—the Fur Trade Rendezvous. We noted Hobbyists suddenly thirsting for knowledge on how to make lodges and period-correct attire. I mentioned my hope to make a traditional buffalo hide tipi, not a canvas tipi. Laubin responded that no one would make a hide tipi; hides were unavailable and Indian women who knew, died long ago. I took his comment as a challenge and began studying those few existing hide tipis in museum collections. Five covers, none complete, made it difficult to determine how hides were placed to be sewn. A eureka moment came when I noted what seemed to be repairs adjacent to swallowtail fringe. It did not make sense to place fringe by a repair. Then I noticed “repairs” with fringe always on opposite sides by fronts of buffalo hides. It suddenly revealed that buffalo were skinned differently long ago on the front legs and the swallowtail dangle was a result of hide trimmed to join the leg to the neck for “squaring” the hide. I was now able to complete my first tipi, an 18-foot. The St. Louis Arch being built heard of my tipi and wished to purchase it, but discovered my tipi poles were too tall for their museum’s ceiling. They asked for a smaller buffalo hide tipi, which began my interest in creating hide tipis for museums. To honor Laubin’s love, and my interest for the old days, I authored Buffalo Hide Tipi of the Sioux and video Lakota Quillwork, Art and Legend to show beauty and romance of the first Lakota home—the hide tipi.

By Larry Belitz, Plains Indian Material Culture Consultant

December 1, 2023

KIOWA BRAIN-TAN THEIR FIRST BUFFALO HIDE

In mid-June a delegation of Kiowa tribal leaders traveled from Oklahoma to the Larry Belitz ranch in the Black Hills to experience brain-tanning buffalo hides. Kiowa history reveals the tribe formerly resided around the Hills in the mid-1600s until pressured southward by the Sioux.

The group's mission was to reintroduce buffalo tanning to the tribe after an absence of over a century. Heading homeward they would retrace their ancient journey from the Hills to various sites before returning to their reservation in Oklahoma.

Sonny, Jesse, Lynda, Dorothy, Rachel, Jim, Debbie, Larry

(Dorothy Whitehorse DeLaune was born in a tipi)

The members learned to stretch a fresh buffalo hide and clean it of fat, meat and membrane using fleshers. The following days were devoted to scraping off buffalo wool with elk horn scrapers, rubbing buffalo brains into the hide and stretching it to made it soft.

Staking a buffalo hide to stretch it flat.

On their last morning, the group learned how to place hides for making a tipi cover. The Kiowa workers sinew-sewed, using tendon threads they prepared, to join the first hides for a tipi.

Connecting two buffalo hides by using sinew threads they prepared.

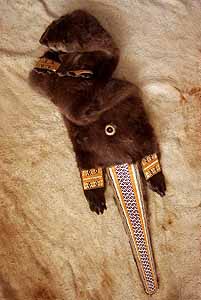

Lewis and Clark: Gift of the Mandan Traveling Museum

Lewis and Clark: Gifts of the Mandan is a traveling museum featuring authentic replicas of the artifacts given to Lewis and Clark by Plains Indian tribes during the explorers’ stay at a Mandan village. This collection, around 1805, was eventually shipped to Thomas Jefferson, who was President at the time.

As a bicentennial celebration of the legacy of these artifacts, Larry Belitz was able to recreate many of them to be displayed in a traveling museum. Pictures of this exhibit, taken by photographer Franz Brown, are shown below.

A Cheyenne Dream Fulfilled

Left to right: Tee Jay Littlewolf, Lori Killsontop, Larie Clown, Rebekah Threefingers, Maria Russell, Jodi Waters and kneeling is Victoria Haugen

For over a century, the Northern Cheyenne dreamt of constructing a buffalo hide tipi. The last time such a tipi was constructed was about 1877 when herds of buffalo were on the verge of extinction and reservations were established. The dream of completing a hide tipi was realized August 21, 2014, when seven Cheyenne women from Chief Dull Knife College in Montana erected a buffalo hide tipi they helped complete.

The morning of June 11 began the task of tanning the first buffalo hide for a tipi under the direction of Larry Belitz. The hide was laced onto a frame so buffalo leg bone fleshers used by the workers could jab fat and meat from the skin. After the hide had dried to become stiff rawhide, the hair (wool) was scraped off using an elk horn scraper. The next day the rawhide was soaked in water to become pliable and buffalo brains were rubbed into the hide.

After brains had time to soak into the skin, holes were sewn with sinew and the hide laced again to a frame. The hide was pushed and staked to stretch the fibers so the skin would be soft and not stiff when completely dried.

After working the skin for hours on the frame, the hide was unlaced and another technique used--tossing youngsters into the air. Such a sport was enjoyed a century earlier. As a child sat in the center of the robe, those holding the edges of the hide pulled in unison to send the person into the air. After a dozen tosses, another child got a turn. This unique method stretched the hide, while having fun!

After a month for Belitz to tan five additional buffalo hides, the group returned in August to sew the hides together. The sewing involved poking holes with an awl to attach hides together at their edges using sinew thread. This sewing required three days.

Lodgepole pines were cut and peeled, chokecherry lacing pins carved and a buffalo hide tying robe braided to have everything ready for the dedication. On the morning of the dedication, the tipi was traditionally honored by having seven military veterans walk barefoot across the tipi cover while an honoring song was sung.

Cheyenne elders spoke about the importance of this tipi. The women next set up the pole framework, wrapped the hide cover around the poles, pinned the right and left sides together and inserted smoke flap poles. Alan Blackwolf, Keeper of the Northern Cheyenne Sacred Buffalo Hat, then smudged the tipi. The crowd joined hands around the new tipi and a prayer was offered. Accompanied by drumming and singing from two Cheyenne elders, the group danced in a circle to a Friendship Dance.

To bring this long-sought dream into reality required the effort of the Cheyenne workers and behind-the-scene work of the following: grant writing by Dana Kizzier, Dr. Richard Littlebear of Chief Dull Knife College, Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation Board of Directors and Larry Belitz who tanned the needed buffalo and directed the tipi-making. Funding was essential for the project and came from the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community, Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund and Wyoming Humanities Council.

By Larry Belitz, Plains Indian Material Culture Consultant